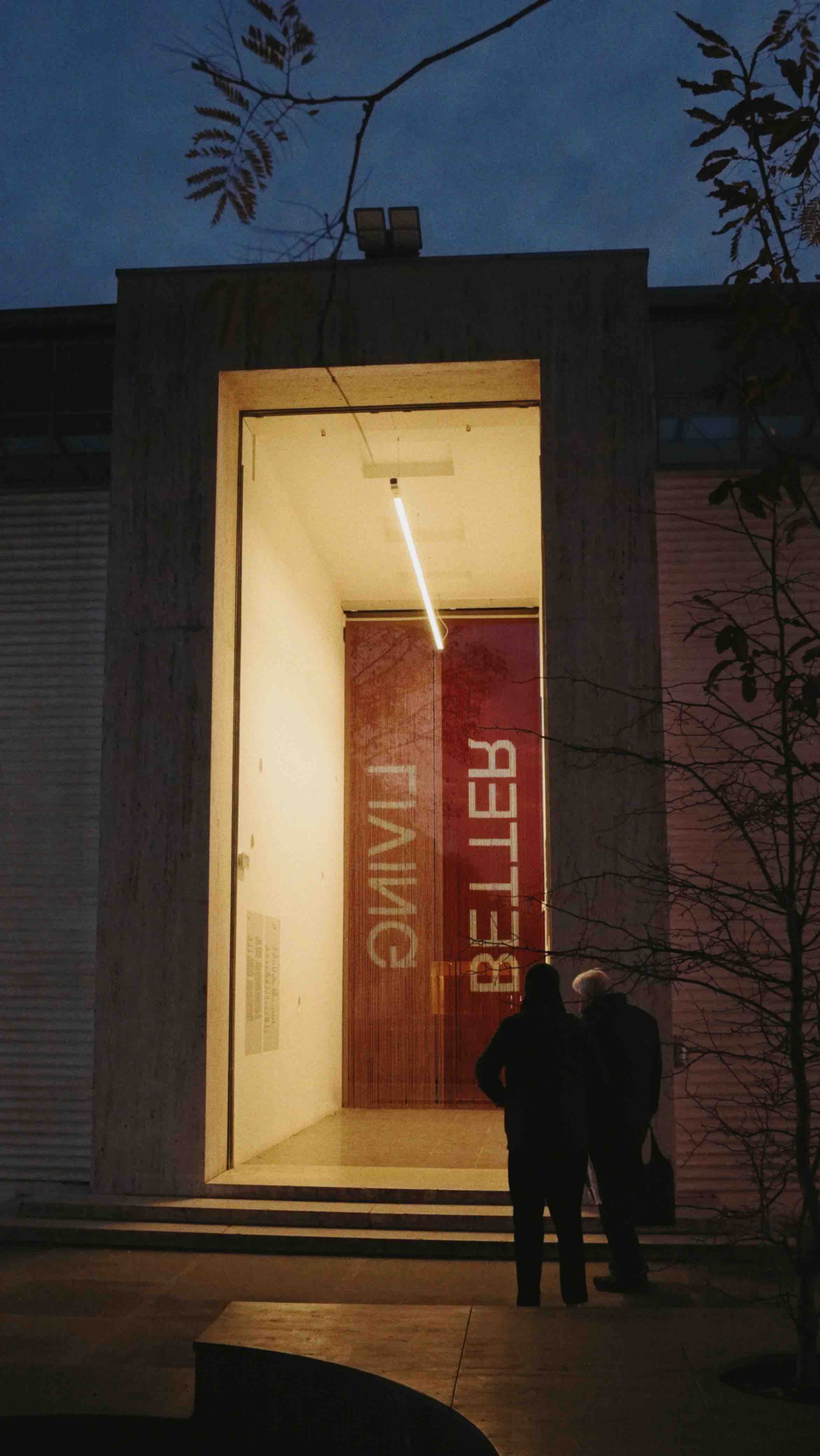

Carlo Ratti: Core Statement

Over 750 participants from a wide range of disciplines were invited to contribute to this year's event. The main focus of the exhibition was the climate crisis and people, with the built environment at its core. The theme of the biennale Intelligens: Natural, Artificial, Collective was built around the belief that ARCHITECTS will be at the centre of future negotiations and actions to adapt the world to our new climate. Although technology could support this, we need to draw on all types of intelligence to develop solutions.

"Architects need to refocus on adapting urban environments for our new climate. Mitigation has been a traditional way for architecture to engage with climate since the 90s and we need to continue mitigation.

When everybody's talking about AI, we talk about NI. There is so much more intelligence – in biology, in the environment, and in the existing built environment.

For example, Venice — where the gathering takes place — was not originally designed for humans. But people transformed it to make it livable, and today movable dams are one of the ways the city adapts to rising sea levels.

That's why we've got so many beautiful teams including architects, designers, planners, engineers, working together with scientists, Nobel Prize winners, computer developers, mathematicians, social researchers and others, — we really have a lot of interdisciplinarity around the table. That’s the first step to ensure that the common language is being developed and this language is inherently more accessible to many people.”

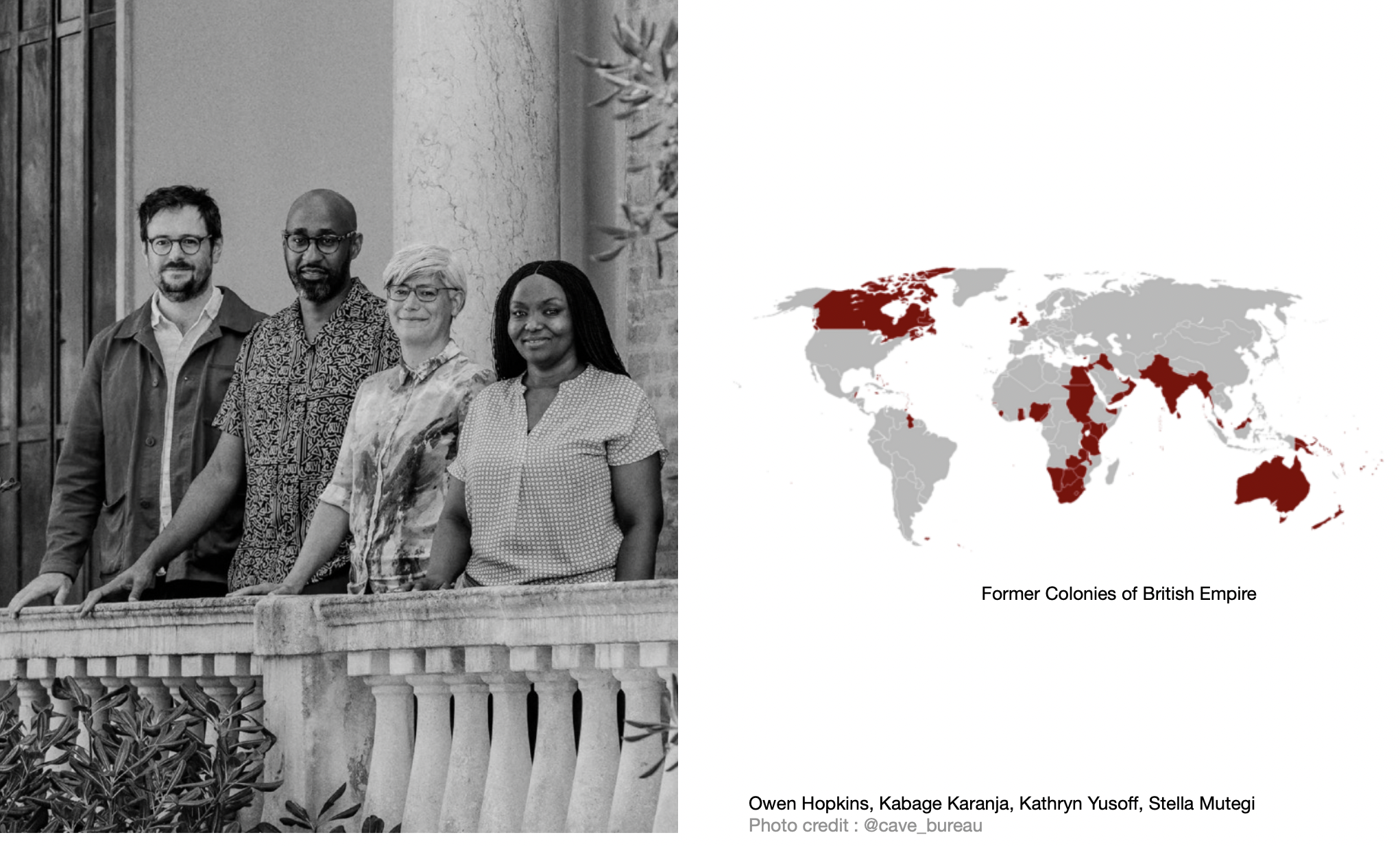

GREAT BRITAIN: WE INVITED KENYA TO BE PART OF A SHARED VOICE

Commissioner: Sevra Davis, British Council

Curators: Owen Hopkins, Kathryn Yusoff, Kabage Karanja, Stella Mutegi

Exhibitors: Cave_bureau, Palestine Regeneration Team (PART), Mae Ling Lokko & Gustavo Crembil, Thandi Loewenso

A marginal collaboration between architectural curators from Britain and Kenya, its former colony.

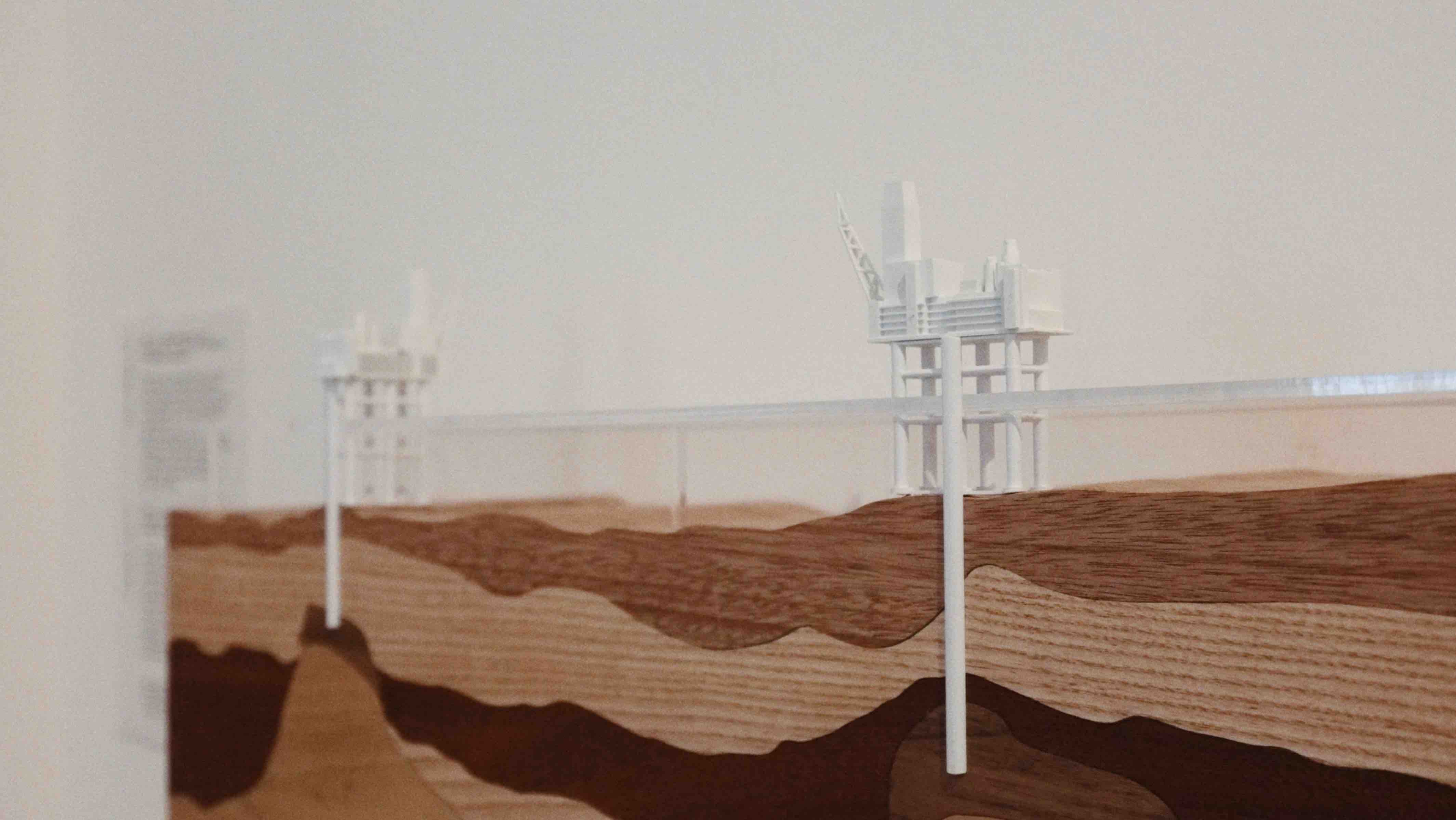

Their joint research aimed to reimagine the relationship between architecture and geology, people and land. The project explores how architecture is implicated in ongoing ‘empires of geology’ defined by extreme forms of extraction that contribute to inequality, injustice, and environmental degradation, while also recognizing that architecture offers opportunities for repair, reparation, and renewal.

Wars and political conflicts are always fights for resources, extraction, and the exploitation of earth materials, which, in turn, shape history. At the exhibition, in the main atrium, there is a graphic line showing different countries responsible for carbon dioxide emissions within the building industry.

The main installation covering the exterior of the British pavilion with beads, made by Maasai women in Kenya, speaks about architects ignored by history because they lacked formal education or were not born in privileged countries. It takes us back to vernacular building practices. Often, Africans have neglected traditional construction methods because the focus was on colonial ideology. Architecture in the colonies was conditioned to value Western building techniques over sustainable local ones. For example, in the façade bead installation, charcoal — widely used in Africa — is actually made from recycled vegetable waste.

In terms of decolonization and reparation, the research highlights collaborations between Britain and Kenya, France and Cameroon, Germany and Angola, Belgium and Congo, and the Netherlands and South Africa. This is especially important today, as we continue to witness economically dominant countries showing little interest in small independent countries on the political map while continuing to extract resources from foreign lands.

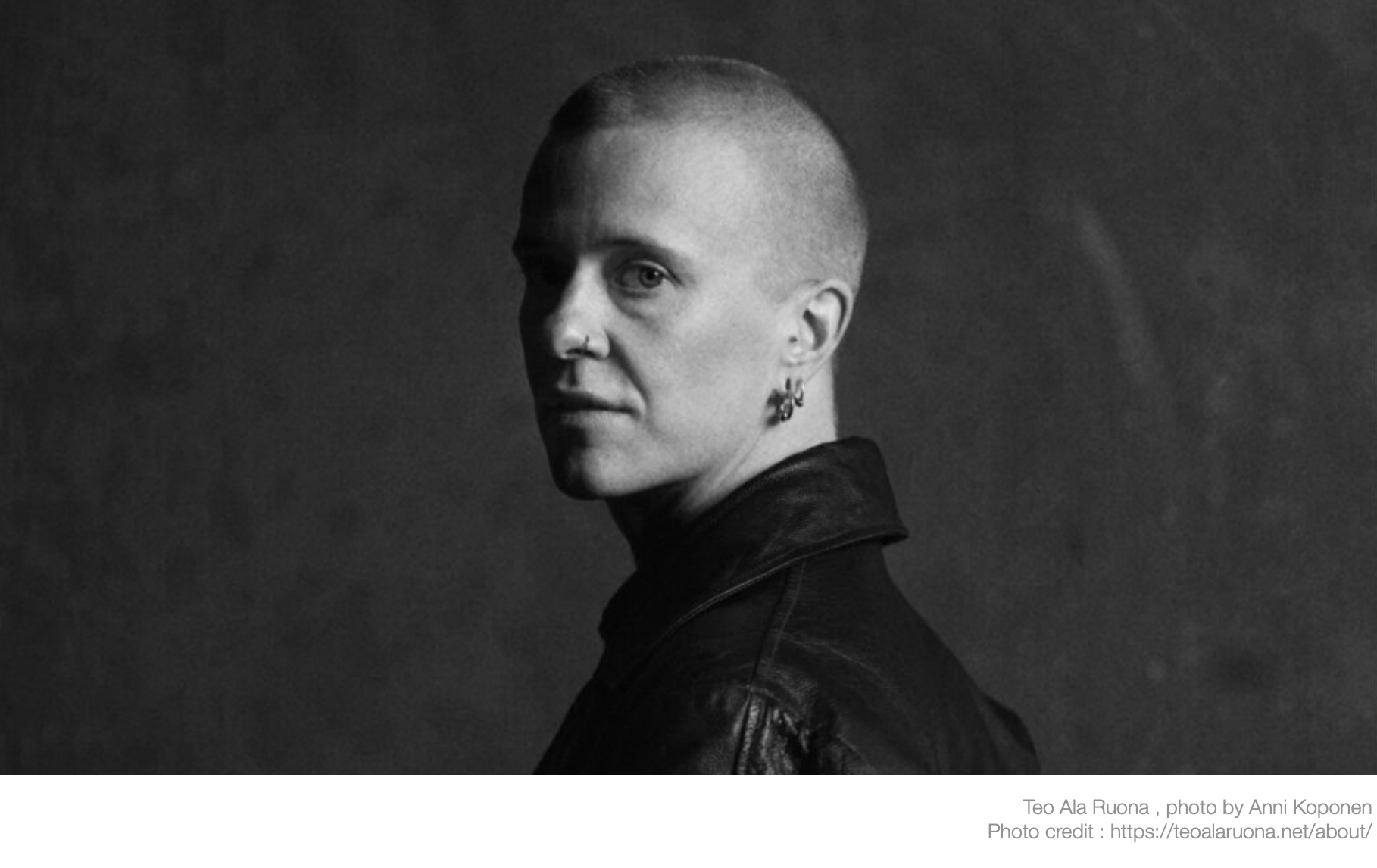

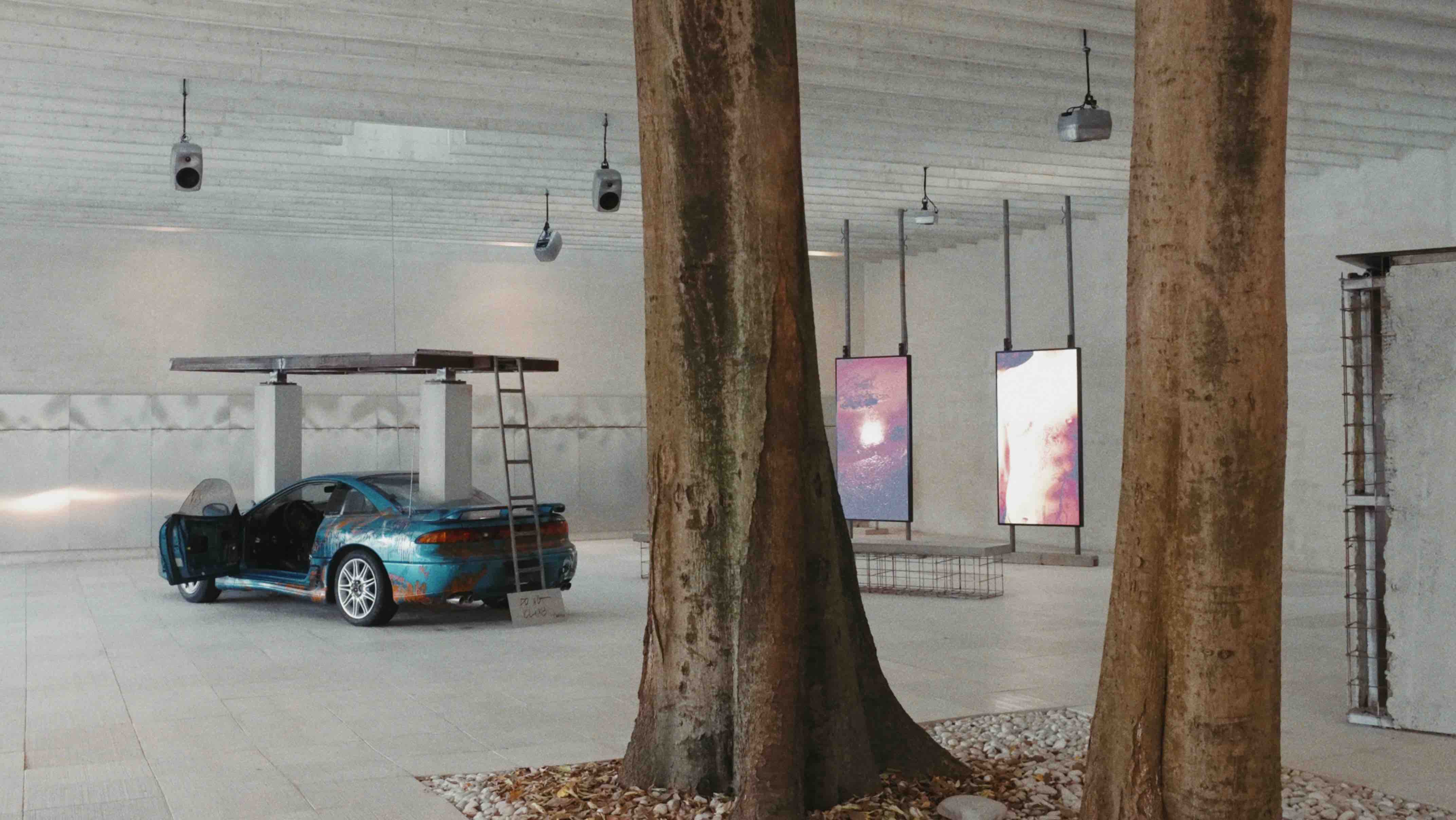

NORDIC COUNTRIES (FINLAND, NORWAY, SWEDEN): ON TRANSGENDER ARCHITECTURE

Commissioners: Carina Jaatinen, Architecture & Design Museum Helsinki, Finland; Yngvill Aagaard Sjöösten, The National Museum of Norway; Karin Nilsson, ArkDes, Sweden

Curator: Kaisa Karvinen

Exhibitors: Car installation by Teo Ala-Ruona

The presented project is a combination of the ecological crisis, fossil fuel dependency and human rights.

The way we think about bodies manifests in the way we design and build.

"Looking at architecture through the lens of trans experience allows us to critically examine the invisible norms and categories embedded in the built environment. As we begin to question the bodily norms architecture is grounded on, other assumptions start to unravel as well, not only those related to gender or identity, but also larger cultural frameworks, such as architecture's deep entanglement with fossil fuel-based systems.

The Nordic Pavilion (designed in 1962 by Norwegian architect Sverre Fehn), as a modernist icon, embodies architectural ideals such as purity and neutrality – norms that still hold influence but now require critical re-evaluation in the face of climate collapse and the growing demand for justice and equity”. — Kaisa Karvinen in an interview for Dezeen.

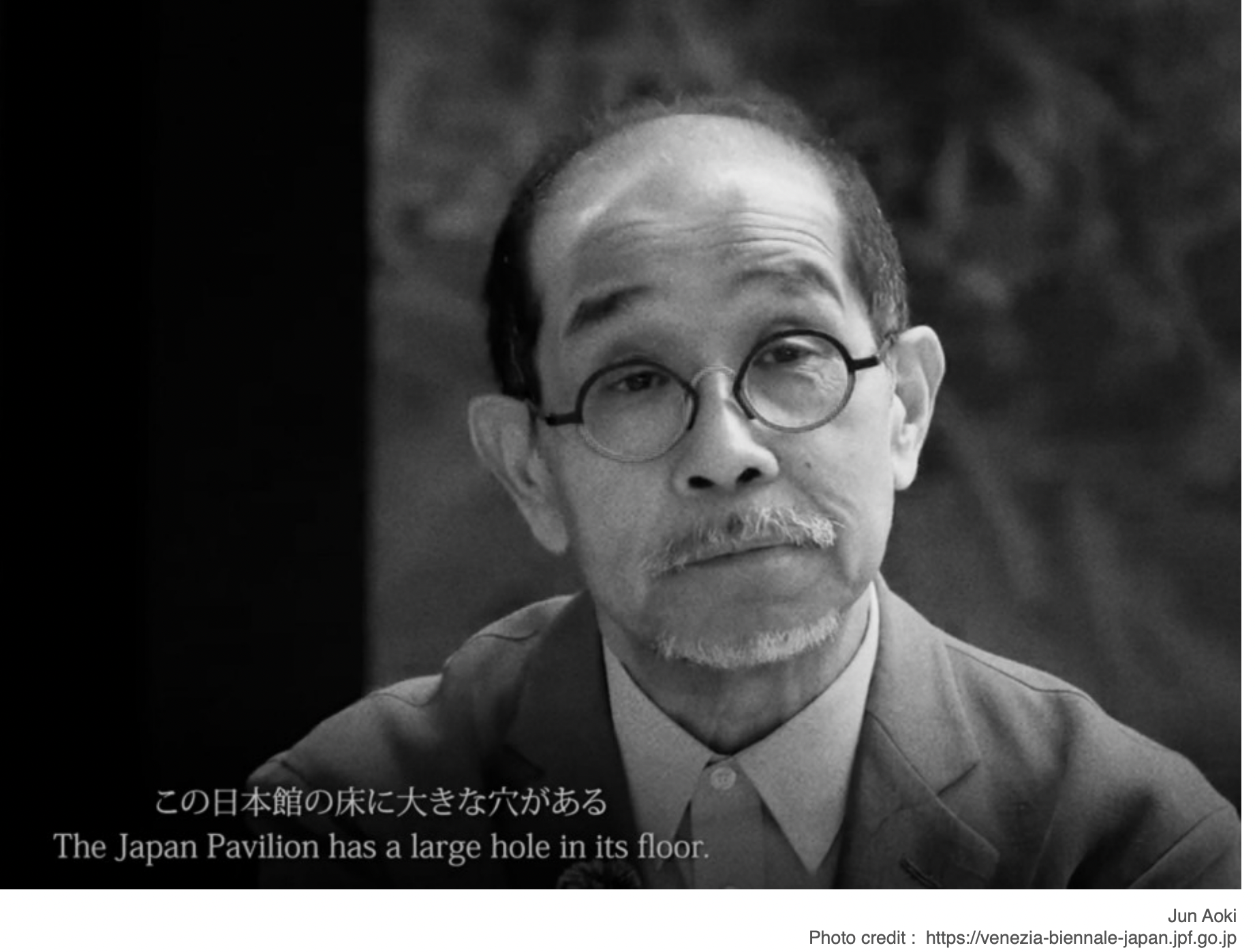

JAPAN: THE TRUTH IS IN THE DIALOGUE

Commissioner: The Japan Foundation

Curator: Jun Aoki

Exhibitors: Tamayo Iemura, Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura, SUNAKI (Toshikatsu Kiuchi, Taichi Sunayama)

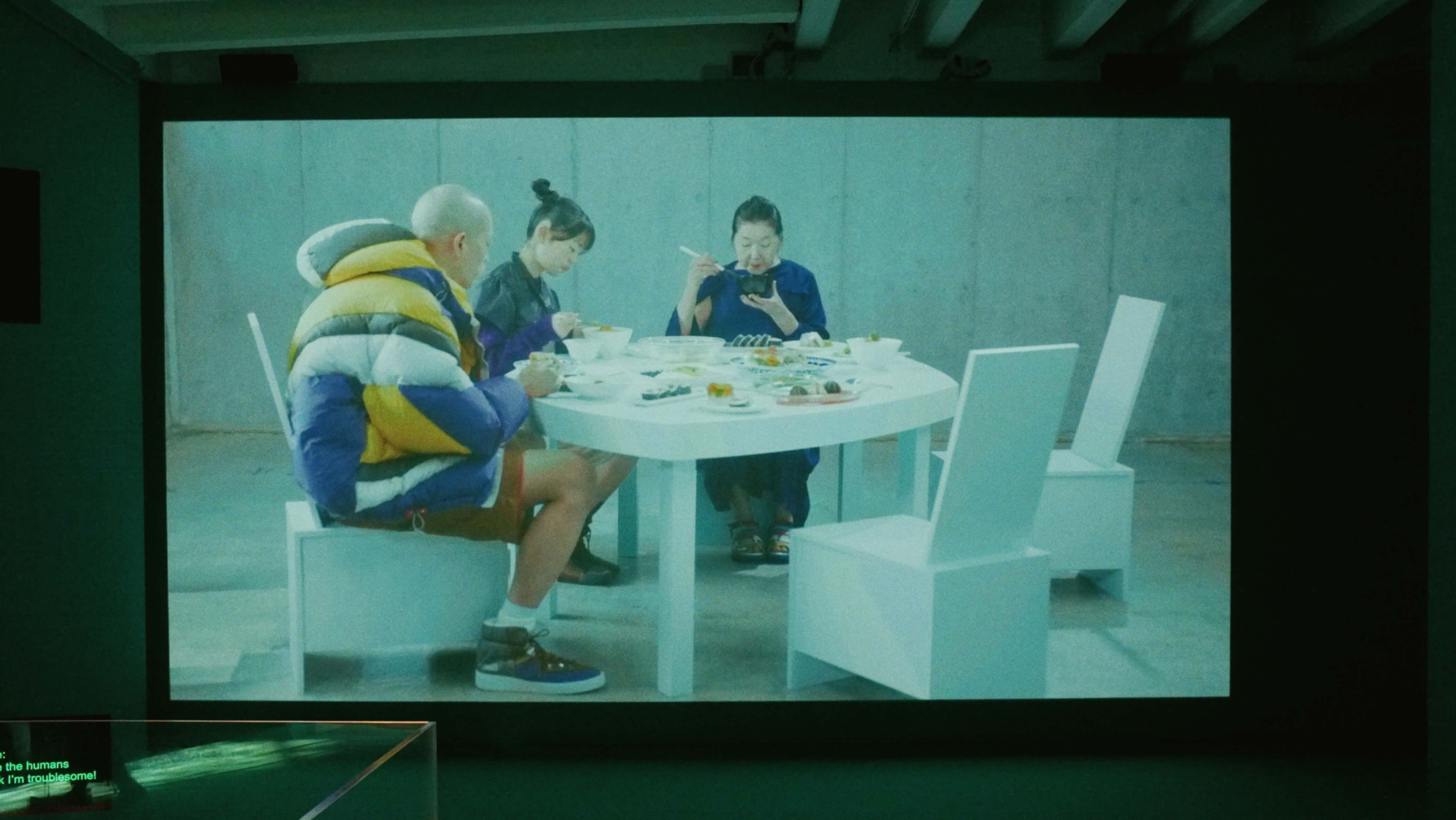

Amid exponential advances in digital technology, the whole world is currently gripped by fear that in the very near future, generative AI will completely change the facets of our society, our environment, and even our own minds. In particular, with the proliferation of social media, Japan seems to be heading toward a politically correct, one-size-fits-all, mediocre society that is merely defined by a lack of mistakes or flaws.

It is true that generative AI provides answers with the least error, derived from the synthesis of existing data. We tend to perceive these as the “correct” answers. However, if we continue down that path, we risk a society in which humans defer to generative AI, and AI, rather than humans, becomes the subject. Nonetheless, Japan has a history with the philosophy of ma, or “in-between space.” Beyond its literal meaning of a gap or interval, ma originally referred to the tension contained in the responses (dialogue) between two things, and the concept of that tension potentially behaving as an imaginary subject. In Japanese, ma is related to the word “truth,” which refers to creating resonance while maintaining tension.

Following that tradition, it may be worth exploring the imaginary “in-between” — the dialogue between humans and generative AI — rather than treating one or the other as the subject. Putting such an attempt into practice is precisely what the theme of the exhibition proposes. Humans make mistakes, but so does generative AI. Interactions between these mistakes may give birth to original “creations” belonging neither to humans nor to AI. The idea is to establish productive ways of interacting with generative AI while it is still in its earliest stages of learning, and to apply these methods to directing its future evolution.

AI tries to approach a world where, unlike humans, it lacks a body. The hole in the first floor of the pavilion (built in 1956 and causing regular problems in exhibitions) this time plays the role of connecting two worlds, while also representing limited perception: it is impossible to know everything. Through this hole, natural light enters the dark capsule of the first floor. Meanwhile, on the ground floor, a plaster installation with natural flaws houses a plant that can be watered. In the rationality of this physical object, we recognize our existence as human beings.

CANADA: GOING MICRO

Photo credit: canadianarchitect.com

Commissioner: Canada Council for the Arts

Curator/Exhibitor: Living Room Collective (Andrea Shin Ling, Nicholas Hoban, Vincent Hui, Clayton Lee)

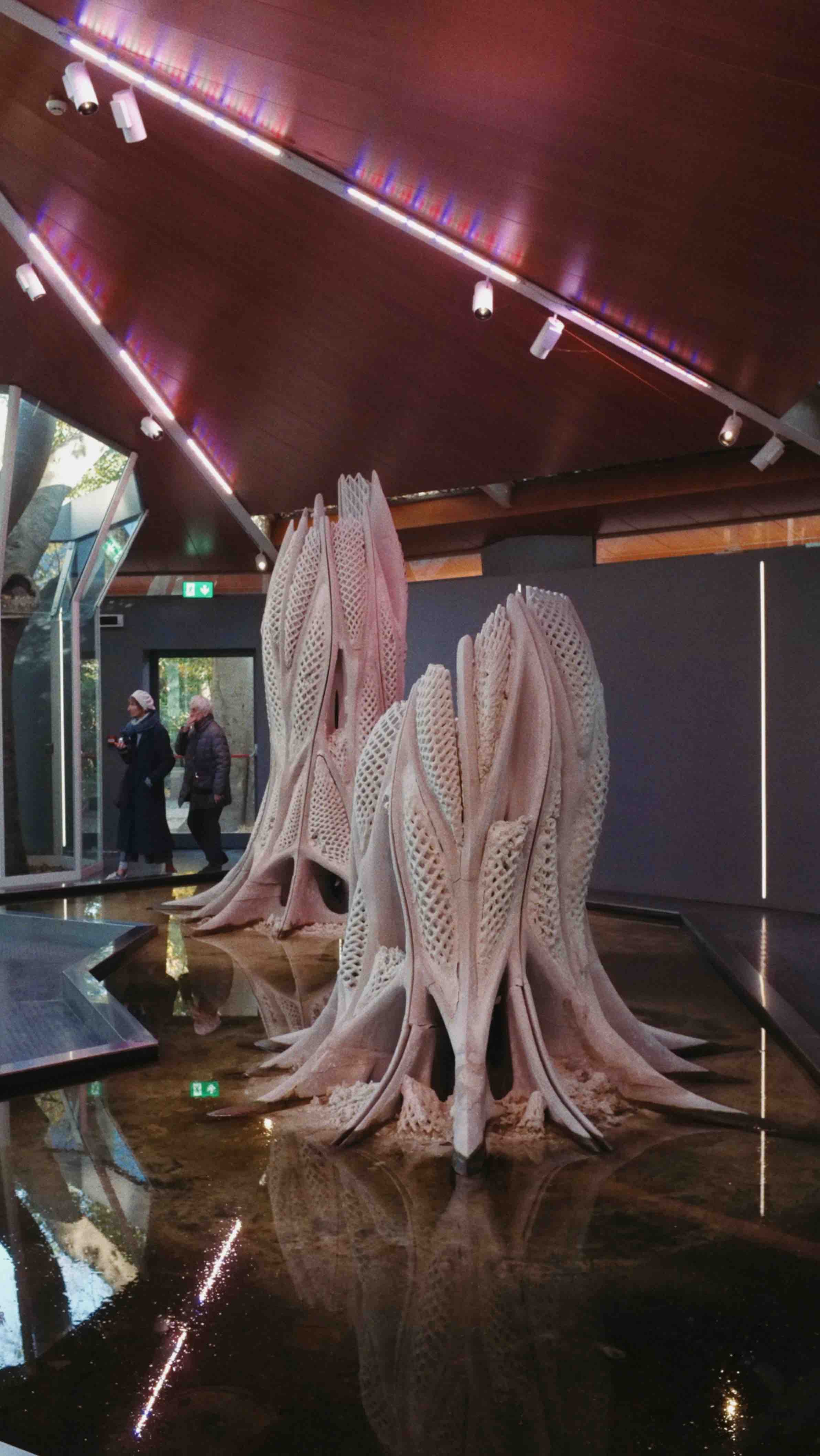

Canada suggests a biological approach to ‘regenerative design’ using live cyanobacteria — picoplankton — which have the capacity to strengthen materials by absorbing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide.

The research team has merged two ancient metabolic processes for picoplanktonics: photosynthesis and biocementation. For the former, they use cyanobacteria, one of the oldest groups of bacterial organisms on the planet.

.jpg)

“Cyanobacteria are among the first photosynthetic organisms and are believed to be responsible for the Great Oxygenation Event, where 2.4 billion years ago, the atmosphere transformed from a high CO2 environment to a high O2 environment because of photosynthesis,” — Andrea Shin Ling explains. — They can also produce biocementation, or the process of capturing carbon dioxide from air and turning it into solid minerals, like carbonates. Because of this, the resulting minerals act like ‘cement’ and can store the carbon permanently, keeping it out of the atmosphere.

SPAIN: NATURE DOES NOT PRODUCE WASTE

Commissioner: MIVAU (Ministry of Housing and Urban Agenda), AECID (Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo), AC/E (Acción Cultural Española)

Curators: Roi Salgueiro Barrio, Manuel Bouzas Barcala

Exhibitors: Alejandro Muiño, Ana Amado, Ane Arce Urtiaga, Anna Bach, Aurora Armental Ruiz, Carla Ferrer, Carles Gabriel Oliver Barceló, Caterina Barjau, Daniel Ibáñez, David Lorente Ibáñez, David Mayol Laverde, Emiliano López Matas, Elisabet Capdeferro Pla, Elizabeth Abalo Díaz, Eugeni Bach, Iñigo Berasategui Orrantia, Irene Pérez Piferrer, Gonzalo Alonso Núñez, Jaume Mayol Amengual, João Branco, José Fernando Gómez, José Toral, Josep Camps Povill, Josep Ferrando, Josep Ricart Ulldemolins, Juan Palencia de Sarriá, Juan Antonio Sánchez Muñoz, Juan Carlos Bamba, Lucas Muñoz Muñoz, Luis Díaz Díaz, Mar Puig de la Bellacasa, Manel Casellas Oteo, Marc Peiro Sempere, María Azkarate, Marta Colón de Carvajal, Salís, Marta Perís, Milena Villalba, Mireia Luzárraga, Mónica Rivera Martínez, Paula del Río, Olga Felip Ordis, Pau Munar Comas, Pedro García Hernández, Ramon Bosch Pagès, Roger Tudó Gali, Sergio Sebastián Franco, Stefano Ciurlo, Vincent Morales Garoffolo, Xavier Ros Majó.

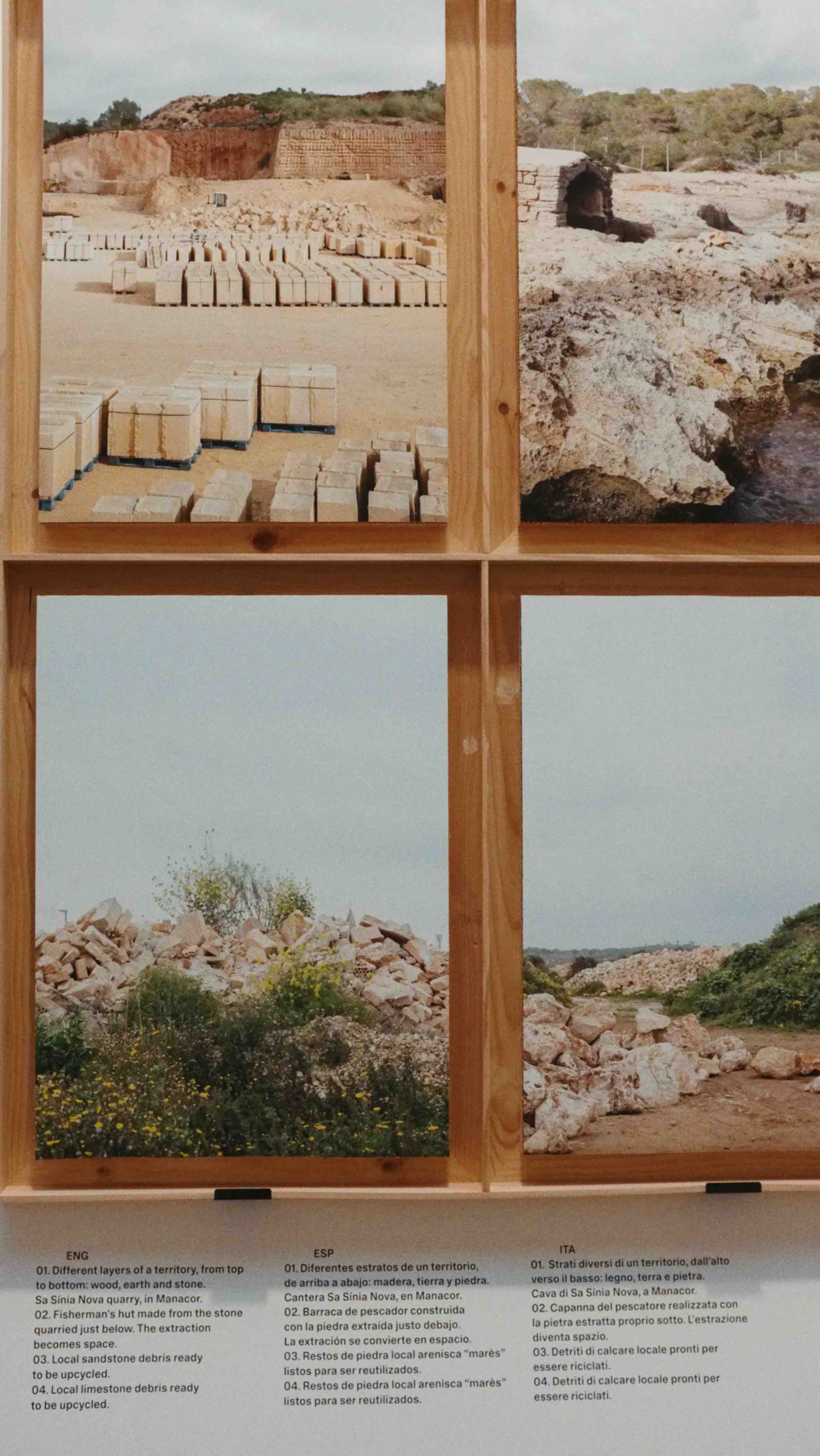

In a manufactured world, the construction sector is one of the key players in the climate crisis, responsible for 37% of global carbon dioxide emissions. If nature does not produce waste, and all materials participate in a continuous cycle, shouldn’t architecture try to minimize the consequences associated with their production? Independent of scale, clients, or materials, with will, architecture can be an active part of positive climate change.

The curators of the pavilion invited several teams of leading architects to present practical studies on sustainability using local materials. In this review, a social housing solution developed by one of the teams — architects Carles Oliver and Xim Moyá (Barcelona) — is selectively presented.

The project’s defining characteristics were minimizing waste during construction, reducing carbon emissions, lowering cooling and heating energy demand, and cutting water consumption over the building’s useful life. The architects also integrated handcraft techniques into the residential construction to foster a sense of community.

AUSTRIA: SOCIAL HOUSING IN EUROPEAN CAPITALS

Commissioner: The Arts and Culture Division of the Federal Ministry for Art, Culture, the Civil Service and Sport of Austria

Curator: Sabine Pollak, Michael Obrist and Lorenzo Romito

The project is an open (both for experts and public) conversation between smart living practices of Vienna and Rome. What can we learn from these cities?

Austria focuses on the housing question. The starting point is a housing crisis spreading across Europe and around the world. Rents are rising to unbelievable levels, highly questionable property policies are spreading, municipal housing is disappearing, neighborhoods are being rented out to tourists, and speculative vacancies have become the norm. For a large portion of the population, living in cities is no longer sustainable. Today, housing is treated as a tradable commodity. The question is: What stance will architecture take on this?

Exploring practices, spaces, and rules in current developments in the area of urban coexistence, Vienna is taking a pioneering role in the question of affordable housing for all.

Both cities, Vienna and Rome, demonstrate different forms of ‘intelligens’ in improving the social and economic efficiency of living in capital cities. Vienna is a city that cares: in a top-down process, the municipality ensures that everyone seeking affordable housing can get it. Rome is the city of ruins, where hard-won, bottom-up processes create informal living spaces with often astonishing forms of self-organization. The Viennese system provides security; the Roman system fosters a reactive and creative civil society. In both cities, innovative ways of living are generated. Overlaying the two systems, we can imagine a new level of cooperation between planners and inhabitants, which could inform future urban strategies for unusual, inclusive, affordable, and climate-friendly forms of communal living.

Cities can and should be places of reconciliation, where not just a privileged minority but everyone has access to affordable, high-quality living. The dialogue between Vienna’s planned, public residential buildings and Rome’s improvised, often spontaneous architecture encourages interdisciplinary collaboration that can provide a climate-friendly, socially just housing model for any city.

AUSTRALIA: THE FEELING OF HOME

Commissioner: Australian Institute of Architects

Exhibitors: Michael Mossman, Emily McDaniel, Jack Gillmer-Lilley, Kaylie Salvatori, Clarence Slockee, Bradley Kerr, Elle Davidson

What does home mean to all around us? Humans and nonhumans, emotional and non-emotional. Do we all have a place where we belong?

Home is where we live, where we love, and where we maintain deep relationships with those closest to us and those who have come from afar. Home is a place of refuge, protection, and memory. Home is where dreams and aspirations live, and where the heart belongs — a place that resonates with these qualities, sharing them with the world. Home is our country, our stories, and songlines in our geology. Home is the step we sit on to look at the stars. Home is a place where we can be ourselves, and that which unites us as a collective. It is a place of belonging that cultivates infinite gratitude.